This piece originally appeared in The Nation under the title “The Ballad of John and J.D.” on January 27, 2011.

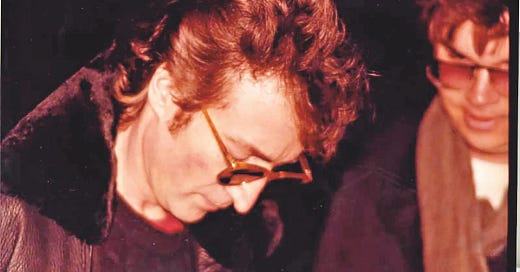

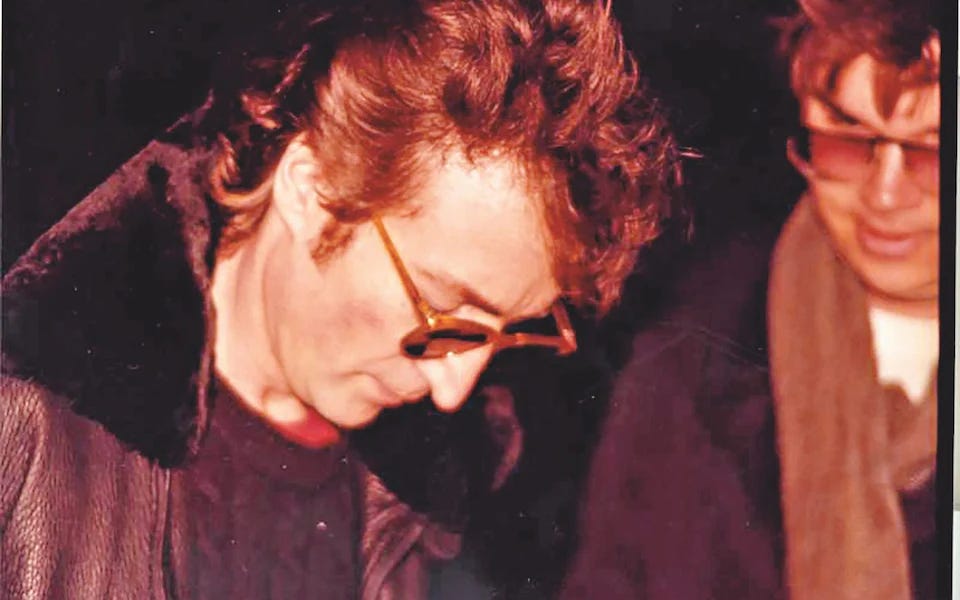

“A local crackpot.” That’s how a New York City cop, quoted by a TV reporter, described the man who had just been arrested for shooting John Lennon at the entrance to the Dakota. The cop turned out to be only half right: Mark David Chapman had come from Hawaii.

I can’t find the remark in any of the accounts of December 8, 1980, but it has stuck with me for thirty years. The cop didn’t appear on camera, but the way the reporter quoted him still makes me think that I’d heard the remark straight from his mouth. Cutting through all the breaking-news urgency, through the anchors and reporters who, having failed to rise to an unthinkable occasion, fumbled for shopworn lines about the man whose music united a generation, the policeman’s words conveyed disgust, dismissiveness, a determination to keep this killer, whoever he was, in his place. Who, the cop was asking, was this nobody to have murdered John Lennon?

Chapman’s identity, as it was pieced together through the following day, was slotted into a narrative predicated on his being a nobody. He was a fat loser who couldn’t hold a job, the newscasters said, who drifted from place to place, who wrestled with mental problems. Killing John Lennon was Chapman’s shortcut to fame—just as shooting Ronald Reagan would be John Hinckley’s a few months later.

But to Chapman, the nobody was Lennon. Chapman later reportedly said that in the week before the assassination he’d been listening to John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band, the raw and abrasive 1970 record on which Lennon purged his music of the gorgeous harmonies and studio lushness of the Beatles. And yet for everything that was stripped down about the record, it is, like the music it turned its back on, magisterial. The penultimate track, “God,” builds to a close with Lennon’s rising list of denunciations: “I don’t believe in Bible … I don’t believe in Jesus … I don’t believe in Beatles.” “Who does he think he is,” Chapman remembered thinking, “saying these things about God and heaven and the Beatles?”

“I kept wanting to kill whoever’d written it…. I kept picturing myself catching him at it, and how I’d smash his head on the stone steps till he was good and goddam dead and bloody.” That’s not Chapman talking, though he had wished that it was. The voice belongs to Holden Caulfield, the name that Chapman signed in the paperback copy of The Catcher in the Rye that he was carrying with him when he shot Lennon. The signature appeared under the words “This is my statement.” After murdering Lennon, Chapman began reading from J.D. Salinger’s novel, which is what he was doing when the cops found him. A few months later at his sentencing hearing, asked if he wished to give a statement, Chapman offered these lines from Catcher:

Anyway, I keep picturing all these little kids playing some game in this big field of rye and all. Thousands of little kids, and nobody’s around—nobody big, I mean—except me. And I’m standing on the edge of some crazy cliff. What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the cliff—I mean if they’re running and they don’t look where they’re going I have to come out from somewhere and catch them. That’s all I’d do all day. I’d just be the catcher in the rye and all.

Using Caulfield’s words to explain himself was taken as more proof that Chapman, who instructed his lawyer not to mount an insanity defense, was crazy. In any event, at the time it was easier to think Chapman was nuts than to think about the collision of two totems, easier than asking how many members of the American generation that had embraced John Lennon could also feel their adolescent angst was given voice by a book so opposed to everything Lennon and the Beatles had stood for. No one dwelt on that side of the story.

* * *

In the months and years after Lennon’s murder, it was as if the secret life of The Catcher in the Rye came aboveground for the first time since the book’s publication in 1951. It was found in Hinckley’s hotel room after he was arrested, and in 1989 Robert John Bardo had a copy of it on him when he murdered the actress Rebecca Schaeffer. The next year, in John Guare’s play Six Degrees of Separation, the con man protagonist holds forth on the book’s attraction to the violently disturbed, quoting Holden’s remark that his ever-present red hat is a “people-shooting hat.” In Richard Donner’s 1997 thriller Conspiracy Theory, the mere purchase of the book at Barnes & Noble is enough to trip a signal to the computers of an unnamed government agency. Whoever reads Catcher, it seems, is up to no good.

You could say that those events are signposts on the novel’s journey from shared totem to shared joke, or that the journey is part of the postmodern irony we’re all drowning in, when we’ve become too cool to be affected by Holden’s open wound of a psyche. But Catcher has become something even less harmless than a joke or postmodernism: a classic. The generations that once had to read it on the sly, or who saw their teachers face the ire of school boards and parents for assigning it, are now senior citizens or entering late middle age. While the book has retained its status as one of the most-censored books in American schools, that distinction now seems almost quaint. But God help The Catcher in the Rye should it ever stop being persecuted. What better confirmation for Holden’s disciples of the threat still posed by the phonies?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Crackers in Bed to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.